Please NOTE: these are not the complete readings, just those readings not available in the texts you have been asked to acquire for the module. The complete readings for each week are listed on the syllabus (under ABOUT).

WEEK 1

Required

Claude Levi‐Strauss, “The Totemic Illusion”

Suggested

Further Resources

Speaking for Animals, ed. Margo DeMello

Andrew Peynetsa’s Telling of “The Boy and the Deer”: Storytelling and Double Binds, Edwin Smith

Paul Shepard, Identity, The Others: How Animals Made Us Human

Animal of the Week

Also featured in the Weather segment of the new David Attenborough Perfect Planet series on BBC.

The Desert Rain Frog emerges from the sand to absorb moisture from the night fog that envelops sand dunes along the coast between Namibia and South Africa. To swallow food (insects and larvae) it must retract its bulging eyes. Squeaky toy or ferocious beast?

WEEK 2

Required

Carol J. Adams, “The Sexual Politics of Meat”

OzekiYearOfMeat.compressed

(apologies for the quality of this: if you want to see the high res file, let me know and I can email you a link)

Suggested

Plutarch, “The Eating of Flesh”

Animal of the Week

Also featured in the Oceans segment of the new David Attenborough Perfect Planet series on BBC.

The species is active during the day and has been observed hunting fish and crustaceans. It employs complex and varied camouflage to stalk its prey. The normal base color of this species is dark brown. Individuals that are disturbed or attacked quickly change colour to a pattern of black, dark brown, white, with yellow patches around the mantle, arms, and eyes. The arm tips often display bright red coloration to ward off would-be predators. Animals displaying this colour pattern have been observed using their lower arms to walk or “amble” along the sea floor while rhythmically waving the wide protective membranes on their arms. This behavior advertises a poisonous nature: The flesh of this cuttlefish contains a unique toxin.

WEEK 3

Required

Clayton Eshleman, Juniper Fuse (EshlemanSelections)

NOTE on the Eshleman selections: I suggest first reading “Chronologies and Cultures,” pp. 237-241, then “Cave Art Theory,” pp. 125-139. Then the rest, as follows (about 74 pages total). The PDF includes all the relevant Notes and Commentary at the end, often substantial and helpful:

Introduction xi-xxvi

Interface I: “The Separation Continuum” 4-8

Seeds of Narrative in Upper Paleolithic Imagery 29-41

Notes on a Visit to le Tuc d’Audoubert 68-73

Through Breuil’s Eyes 76-77

The Chaos of the Wise 116

Neanderthal Skull 117

A Phosphene Gauntlet 145

Le Combel 146-149

Hybrid Resonance 150-166

Indeterminate, Open 167-173

Images on pp. 180-81, 184-85

Sparks We Trail 195

Upon Emerging from Bernifal 203

Notes

Ted Hughes, “The Thought Fox”

Galway Kinnell, “The Bear” (Kinnell reading the poem)

W.S. Merwin, “Leviathan,” “For a Coming Extinction” (reading here, with preamble, from 5m40), “After the Alphabets,” “The Mole,” “Water Pouring from Clouds” (poem here)

Water pouring from clouds

in the light

of palm forests

large ears motionless

they listen

the elephants

eyes half-closed

to the sound of the heavy rain

their trunks resting on their tusks

Translation of anonymous twelfth century Sanskrit,

with J. Moussaieff Masson

Steve Baker, “Sloughing the Human” (from Zoontologies, ed. Cary Wolfe)

Suggested

Paul Shepard, “Introduction,” The Others: How Animals Made Us Human

ShepardIntroduction

Aaron Moe, “‘learning my steps’: Zoopoetics and Mass Extinction in W.S. Merwin’s Poetry,” in Zoopoetics: Animals and the Making of Poetry

MoeZoopoetics

Further Resources

Lascaux “shaft scene”

Mas d’Azil (and the antler spear-thrower)

“World’s oldest known cave painting found in Indonesia” (Guardian, 13 Jan 2021)

Antony Gormley, How Art Began

Animal of the Week

The addax is a critically endangered species of antelope, as classified by the IUCN. Although extremely rare in its native habitat due to unregulated hunting, it is quite common in captivity. The addax was once abundant in North Africa, native to Chad, Mauritania and Niger. It is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan and the Western Sahara. It has been reintroduced into Morocco and Tunisia.

The addax is amply suited to live in the deep desert under extreme conditions. It can survive without free water almost indefinitely, because it gets moisture from its food and dew that condenses on plants. Scientists believe the addax has a special lining in its stomach that stores water in pouches to use in times of dehydration. It also produces highly concentrated urine to conserve water. The pale colour of the coat reflects radiant heat, and the length and density of the coat helps in thermoregulation. In the day the addax huddles together in shaded areas, and on cool nights rests in sand hollows. These practices help in dissipation of body heat and saving water by cooling the body through evaporation.

“What but the wolf’s tooth whittled so fine

The fleet limbs of the antelope?

What but fear winged the birds, and hunger

Jeweled with such eyes the great goshawk’s head?”

— Robinson Jeffers, “The Bloody Sire”

WEEK 4

Required

Franz Kafka, “Josephine the Singer” / PDF version (different translation)

Deleuze and Guattari, “Becoming-Animal” (excerpt from The Animals Reader; here is the full text, in case you want to consult it for clarification, but you are only expected to read the excerpt)

Helpful, short summary of Deleuze & Guattari’s essay here.

Julio Cortázar, “Axolotl” Word / PDF

More axolotl images

Suggested

Ron Broglio, “A Minor Art: Becoming‐Animal of Marcus Coates,” Surface Encounters: Thinking with Animals and Art

BroglioOnCoates

Alphonso Lingis, “Animal Body, Inhuman Face”

Jacob von Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Men

UexküllForay

NOTE: the relevant text in this PDF is A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Men, pp. 44-135. If you just read the first 26 pages–through “Introduction,” “Environment Spaces,” and “The Farthest Plane”–and maybe skim around a bit in the rest of the text, you will get a good enough sense of Uexküll’s “umwelt” concept.

Further Resources

Kári Driscoll, “An Unheard, Inhuman Music: Narrative Voice and the Question of the Animal in Kafka’s ‘Josephine, the Singer or the Mouse Folk’”

Animals of the Week

Alston’s singing mouse (Scotinomys teguina)

S. teguina is exclusively found in the highland forests of Central America, from Chiapas, Mexico to western Panama, at elevations between 1100 and 2950 meters.[5] Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama. This rodent prefers wet habitats with subtropical climates, and is commonly observed in grassy clearings and rocky areas at the forest edge.

S. teguina is often recognized for its unique vocalization behavior. Both males and females produce vocalizations which are characterized by singing bouts containing both sonic and ultrasonic elements. Male songs tend to be longer than females, but seem to share similar spectral characteristics. Although ultrasonic vocalizations have been demonstrated in numerous rodent species, few display vocalizing bouts as continuous and stereotyped as S. teguina. Because of their length and complexity, these vocalizations have been described as “song”. When singing, the mouse rears on its hind legs and extends its neck, facing upward while producing a stereotypical call of up to 10 seconds. The song is loud, with components audible to humans typically occurring towards the end of the call. The exact function of the singing behavior is not yet well understood, but it is believed to play an important role in social communication.

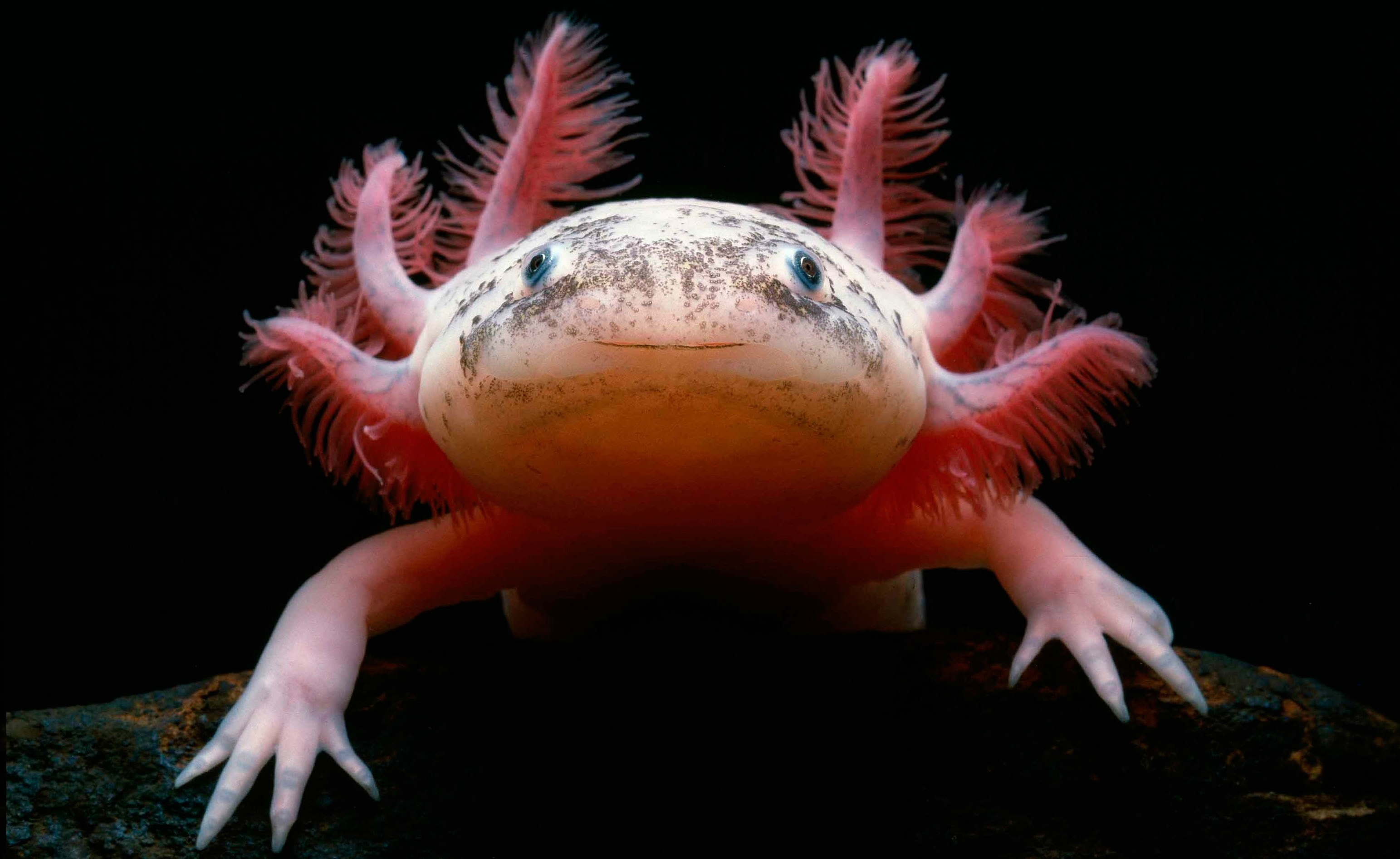

Axolotl

The axolotl (/ˈæksəlɒtəl/; from Classical Nahuatl: āxōlōtl [aːˈʃoːloːtɬ], Ambystoma mexicanum, also known as the Mexican walking fish, is a neotenic salamander related to the tiger salamander. Although colloquially known as a “walking fish”, the axolotl is not a fish but an amphibian. The species was originally found in several lakes, such as Lake Xochimilco underlying Mexico City. Axolotls are unusual among amphibians in that they reach adulthood without undergoing metamorphosis [i.e. exhibit neoteny]. Instead of taking to the land, adults remain aquatic and gilled.

WEEK 5

Suggested

Jeremy Bentham, “Principles of Morals and Legislation”

Peter Singer, “Equality for Animals?” (in 2nd edition of The Animals Reader: you need to get the text from a copy in the library, if you do not own one).

Tom Regan, “The Nature and Importance of Rights” (same as above).

Martha Nussbaum, “What We Owe Our Fellow Animals” (NYRB, 10 March 2022)

— a concise rundown on the latest in animal cognition, emotion and culture and grounds for a new theory of justice for animals (CA or the Capabilities Approach)

See also: Nussbaum, “A Peopled Wilderness” (NYRB, 8 December 2022)

— discussion of ‘the predation problem’ and an argument for ‘modest intervention’ with predation based on the ethical indefensibility of humans renouncing stewardship:

“If humans try to renounce stewardship, in a world where they are ubiquitously on the scene, shaping every habitat in which every animal lives, this is not an ethically defensible choice or one that promotes good animal lives. The only options before us, in the world as it is, are types and degrees of stewardship.”

Further Resources

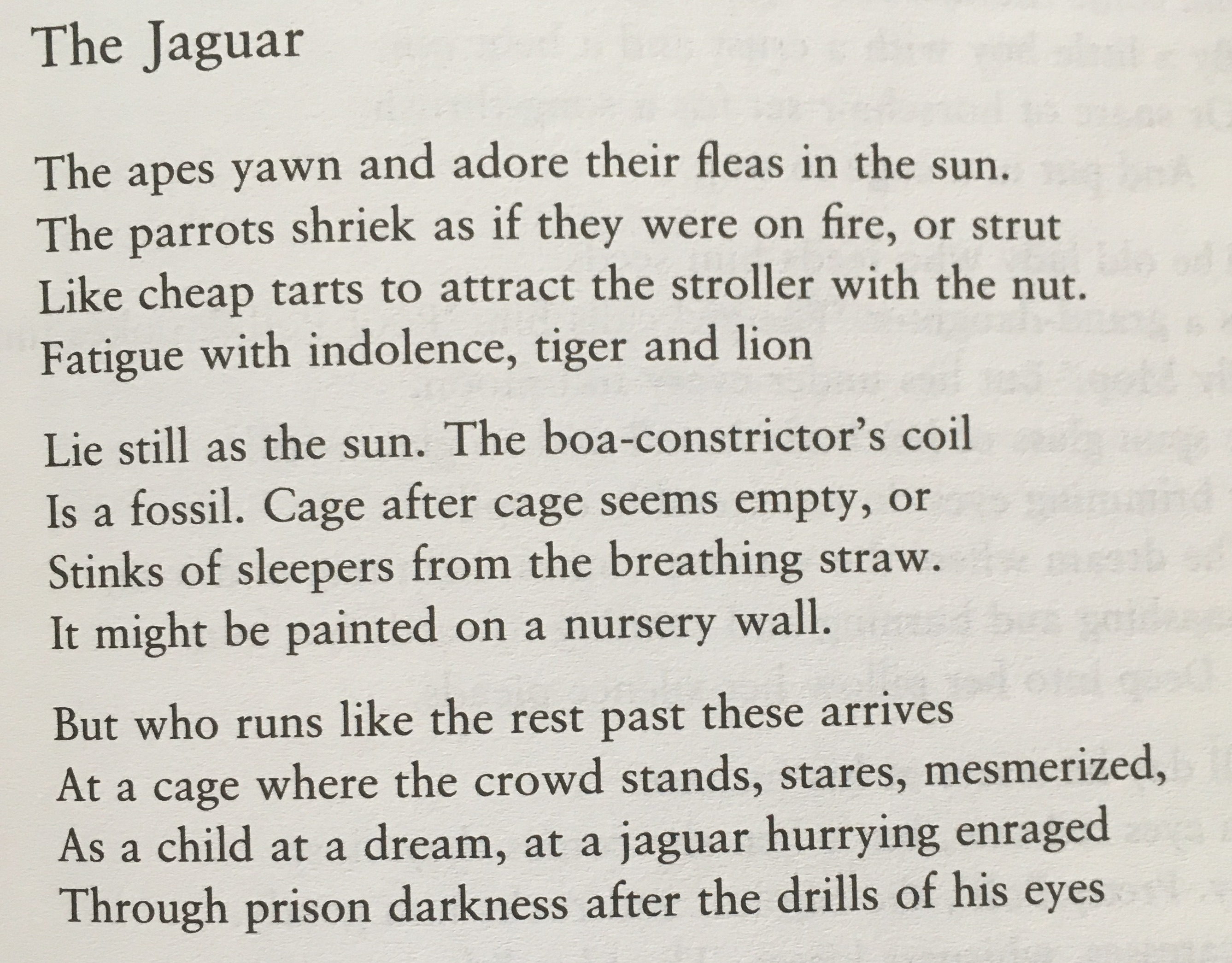

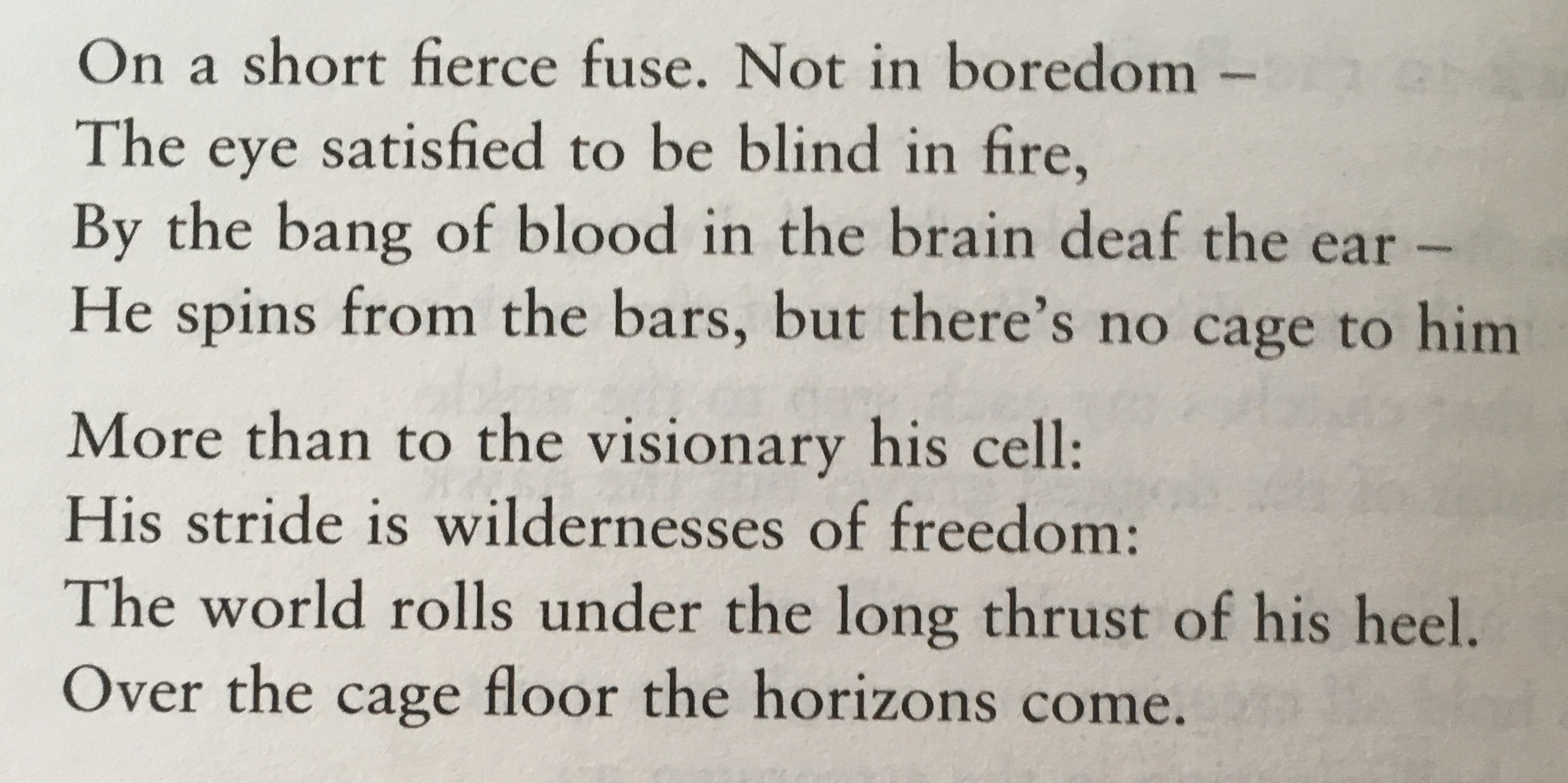

“Hughes is writing against Rilke . . . [The jaguar] is elsewhere because his consciousness is kinetic rather than abstract: the thrust of his muscles moves him through a space quite different in nature from the three-dimensional box of Newton—a circular space that returns upon itself. . . . Hughes is feeling his way toward a different kind of being-in-the-world, one which is not entirely foreign to us, since the experience before the cage seems to belong to dream-experience, experience held in the collective unconscious. In these poems we know the jaguar not from the way he seems but from the way he moves. . . . The poems ask us to imagine our way into that way of moving, to inhabit that body.

“With Hughes it is a matter—I emphasize—not of inhabiting another mind but of inhabiting another body. That is the kind of poetry I bring to your attention today: poetry that does not try to find an idea in the animal, that is not about the animal, but is instead the record of an engagement with him. . . .

By bodying forth the jaguar, Hughes shows us that we too can embody animals—by the process called poetic invention that mingles breath and sense in a way that no one has explained and no one ever will. He shows us how to bring the living body into being within ourselves. When we read the jaguar poem, when we recollect it afterwards in tranquillity, we are for a brief while the jaguar. He ripples within us, he takes over our body, he is us.” (J.M. Coetzee/ Elizabeth Costello, “The Poets and the Animals”)

Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Panther”

Ted Hughes, “The Jaguar”

Ted Hughes, “Second Glance at a Jaguar”

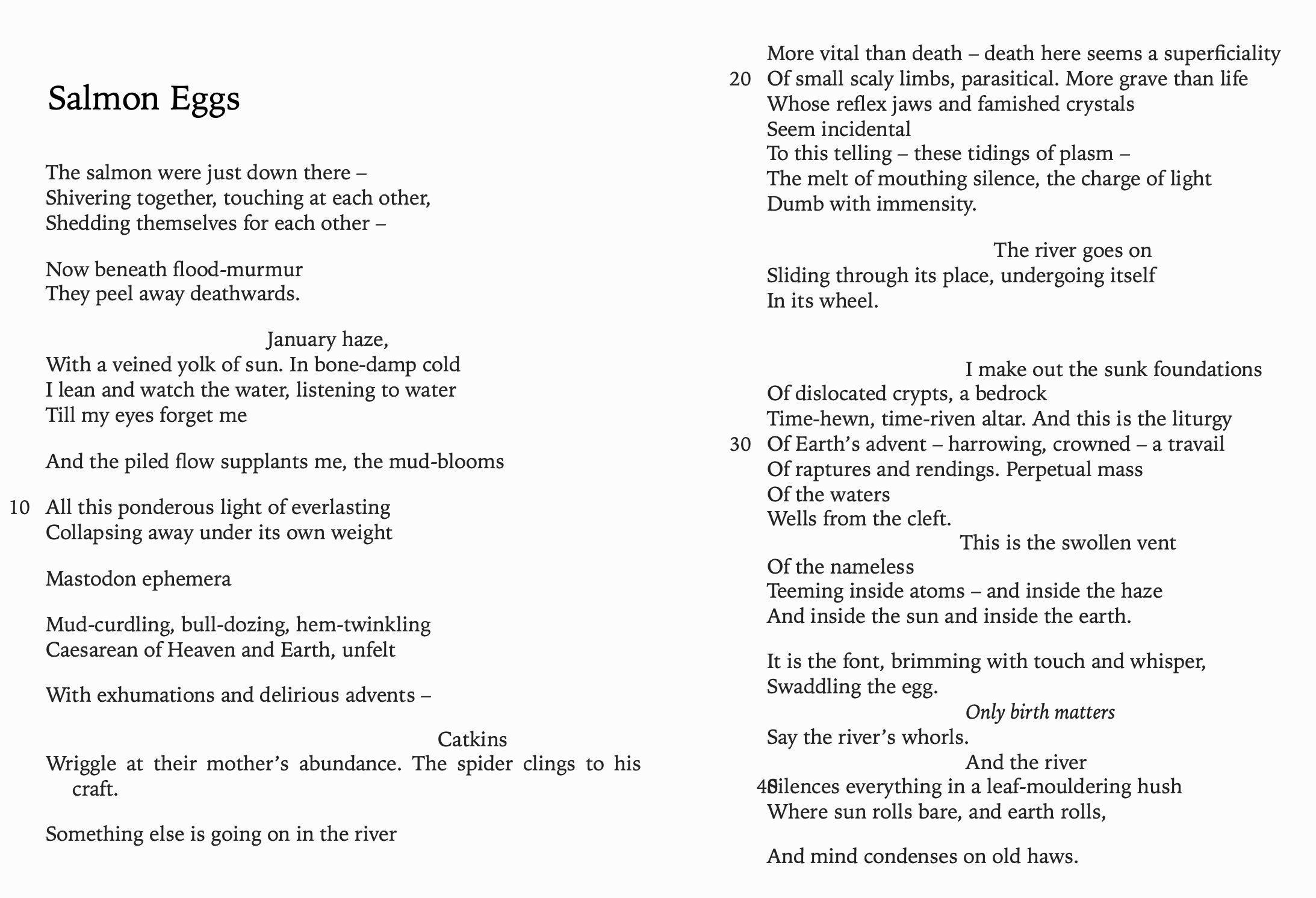

“Nevertheless, the poem that Hughes writes is about the jaguar, about jaguarness embodied in this jaguar. Just as later on, when he writes his marvelous poems about salmon, they are about salmon as transitory occupants of the salmon-life, the salmon- biography. So despite the vividness and earthiness of the poetry, there remains something Platonic about it.” (“The Poets and the Animals”)

Ted Hughes, “Salmon Eggs”

“If I do not convince you, that is because my words, here, lack the power to bring home to you the wholeness, the unabstracted, unintellectual nature, of that animal being. That is why I urge you to read the poets who return the living, electric being to language; and if the poets do not move you, I urge you to walk, flank to flank, beside the beast that is prodded down the chute to his executioner.” (“The Poets and the Animals”)

Animal of the Week

Vampire Bat

Vampire bats are in a diverse family of bats that consume many food sources, including nectar, pollen, insects, fruit and meat. The three species of vampire bats are the only mammals that have evolved to feed exclusively on blood (hematophagy) as micropredators, a strategy within parasitism. Hematophagy is uncommon due to the number of challenges to overcome for success: a large volume of liquid potentially overwhelming the kidneys and bladder.

Unlike fruit bats, the vampire bats have short, conical muzzles. They also lack a nose leaf, instead having naked pads with U-shaped grooves at the tip. The common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus, also has specialized thermoreceptors on its nose, which aid the animal in locating areas where the blood flows close to the skin of its prey. A nucleus has been found in the brain of vampire bats that has a similar position and similar histology to the infrared receptor of infrared-sensing snakes.

A vampire bat has front teeth that are specialized for cutting and the back teeth are much smaller than in other bats. The inferior colliculus, the part of the bat’s brain that processes sound, is well adapted to detecting the regular breathing sounds of sleeping animals that serve as its main food source.

While other bats have almost lost the ability to maneuver on land, vampire bats can walk, jump, and even run by using a unique, bounding gait, in which the forelimbs instead of the hindlimbs are recruited for force production, as the wings are much more powerful than the legs.

Vampire bats also have a high level of resistance to a group of bloodborne viruses known as endogenous retroviruses, which insert copies of their genetic material into their host’s genome.

Vampire bats use infrared radiation to locate blood hotspots on their prey.

Vampire bats tend to live in colonies in almost completely dark places, such as caves, old wells, hollow trees, and buildings. They range in Central to South America and live in arid to humid, tropical and subtropical areas.

Runner up animal of the week: Vampire ground finch (Geospiza septentrionalis).

The vampire ground finch is most famous for its unusual diet. When alternative sources are scarce the vampire finch occasionally feeds by drinking the blood of other birds, chiefly the Nazca and blue-footed boobies, pecking at their skin with their sharp beaks until blood is drawn. Curiously, the boobies do not offer much resistance against this. It has been theorized that this behavior evolved from the pecking behavior that the finch used to clean parasites from the plumage of the booby. The finches also feed on eggs, stealing them just after they are laid and rolling them (by pushing with their legs and using their beak as a pivot) into rocks until they break. Finally guano and leftover fish from other predators additionally serve as diet options.

More conventionally for birds, but still unusual among Geospiza, they also take nectar from Galápagos prickly pear (Opuntia echios var. gigantea) flowers at least on Wolf Island. The reason for these peculiar feeding habits is the lack of fresh water on these birds’ home islands. Nonetheless, the mainstay of their diet is made up from seeds and invertebrates as in their congeners.

Coronavirus and Horseshoe bats (Rhinolophidae):

“ In the spring of 2012, six men who worked clearing bat guano from an abandoned copper mine near the town of Tongguan, in Yunnan Province, fell ill with a severe respiratory disease. They were admitted to a university hospital in Kunming, which sent blood samples from four of the men to the lab of Shi Zhengli, the head of the W.I.V.’s Center for Emerging Infectious Disease. Shi is China’s most famous researcher of bat coronaviruses. Years earlier, she had joined the international team that discovered that horseshoe bats served as a reservoir for a large number of SARS-related viruses. Her lab tested the workers’ serum for possible zoonotic pathogens that Shi and others had previously discovered. Everything came back negative. Three of the workers died.

Between 2012 and 2015, Shi and her team regularly travelled to the Tongguan mine, about a thousand miles from Wuhan. In the evenings, the researchers strung up a mist net at an entrance to the mineshaft, and waited for dusk, when the bats flew out to eat. Throat and fecal swabs were collected from six different species of horseshoe and vesper bats. Ultimately, Shi’s team brought back more than thirteen hundred samples to their lab.

In 2016, Shi and her colleagues published a paper from this work, finding that many of the bats were co-infected by two or more different coronaviruses at the same time. Because the bats live huddled in ever-shifting colonies, they circulate viruses endlessly, even across species, which allows different viruses to recombine, creating novel coronavirus strains: an evolutionary bacchanal. Eventually, Shi’s lab would sequence some portion of all nine SARS-related coronaviruses that were found in samples taken from the Tongguan mine.”

“The Mysterious Case of the COVID-19 Lab-Leak Theory,” by Carolyn Kormann, The New Yorker, October 12, 2021

See also “How China’s ‘Bat Woman’ Hunted Down Viruses from SARS to the New Coronavirus,” by Jane Qiu, Scientific American, June 1, 2020

WEEK 7

Suggested

John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?“

Further Resources

Vicki Hearne, “The Claim of Speech” (poem)

Vicki Hearne, “What’s Wrong with Animal Rights?“

Animal of the Week

Border Collie

The Border Collie is a working and herding dog breed developed in the Anglo-Scottish border region, for herding livestock, especially sheep.

Considered highly intelligent, extremely energetic, acrobatic and athletic, they frequently compete with great success in sheepdog trials and dog sports. They are often cited as the most intelligent of all domestic dogs. Border Collies continue to be employed in their traditional work of herding livestock throughout the world and are kept as pets.

WEEK 8

Required

Cary Wolfe, “In the Shadow of Wittgenstein’s Lion: Language, Ethics, and the Question of the Animal,” pp. 1-11 (“Forms of Language, Forms of Life: Wittgenstein, Cavell, and Hearne”) and pp. 19-34 (“The Animal, What a Word! Derrida [with Levinas]”), Zoontologies

Suggested

Jacques Derrida, “And Say the Animal Responded?”

Jacques Derrida, “The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow)”

DerridaAnimalThatThereforeIAm

Further Resources

Derek Attridge, “Age of Bronze, State of Grace: Music and Dogs in Coetzee’s ‘Disgrace’”

Animal of the Week

Honey bee

A honey bee is a eusocial flying insect within the genus Apis of the bee clade, all native to Eurasia. They are known for their construction of perennial colonial nests from wax, the large size of their colonies, and surplus production and storage of honey, distinguishing their hives as a prized foraging target of many animals, including honey badgers, bears and human hunter-gatherers. Only eight surviving species of honey bee are recognized, with a total of 43 subspecies, though historically 7 to 11 species are recognized. Honey bees represent only a small fraction of the roughly 20,000 known species of bees.

Worker bees cooperate to find food and use a pattern of “dancing” (known as the bee dance or waggle dance) to communicate information regarding resources with each other; this dance varies from species to species, but all living species of Apis exhibit some form of the behavior. If the resources are very close to the hive, they may also exhibit a less specific dance commonly known as the “round dance”.

WEEK 9

Required

Donna Haraway, When Species Meet, “Introduction“

Further Resources

Sherryl Vint, “Speciesism and Species Being in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”

Animal of the Week

Xenobot

A remarkable combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and biology has produced the world’s first “living robots”.

This week, a research team of roboticists and scientists published their recipe for making a new lifeform called xenobots from stem cells. The term “xeno” comes from the frog cells (Xenopus laevis) used to make them.

One of the researchers described the creation as “neither a traditional robot nor a known species of animal”, but a “new class of artifact: a living, programmable organism”.

Xenobots are less than 1mm long and made of 500-1000 living cells. They have various simple shapes, including some with squat “legs”. They can propel themselves in linear or circular directions, join together to act collectively, and move small objects. Using their own cellular energy, they can live up to 10 days.

While these “reconfigurable biomachines” could vastly improve human, animal, and environmental health, they raise legal and ethical concerns.

WEEK 10

Required

Alexis Wright, The Swan Book

Suggested

Thom van Dooren, Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction, pp. 1-18: “Introduction: Telling Lively Stories at the Edge of Extinction” (PDF)

Further Resources

“Fabulation: Toward Untimely and Inhuman Life in Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book,” by Linda Daley

Teachings from Australian First Nations author Alexis Wright

(with thanks to Kate Worth — see especially 11:44-16:27)

“Postscript,” (a poem) by Seamus Heaney

Winged Migration (Jacques Perrin, Jacques Cluzeaud, 2001), Whooper Swans

Animal of the Week

Brolga

Brolgas are one of Australia’s largest flying birds – they stand a metre tall and have a wing span up to 2.4 metres.

They’re one of two members of the Gruidae (crane) family in Australia – John Gould, celebrated ornithologist and artist, once called them the Australian Crane.

Brolgas are best known for their intricate and ritualised dance. Partners begin by picking up grass, tossing it into the air and catching it again in their beaks. The birds then jump up to a metre in the air with their wings outstretched, before performing an elaborate display of head-bobbing, wing-beating, strutting and bowing. Occasionally they stop to trumpet loudly – a spectacular sound!

Both sexes dance year around, in pairs or in groups, with birds lining up opposite each other.

Sandhill Cranes (recording), by Jonathan Skinner